As editors, one of the most common issues we deal with is that of overly long paragraphs. While there are no hard and fast rules, when a paragraph goes on for one or more pages, it’s probably too long. The reader can sometimes get lost, even when the writing itself is otherwise thoughtful and to the point.

My Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a paragraph as “a subdivision of a written composition that consists of one or more sentences, deals with one point or gives the words of one speaker, and begins on a new usually indented line.”

The always useful Purdue OWL notes that, “To be as effective as possible, a paragraph should contain each of the following: Unity, Coherence, A Topic Sentence, and Adequate Development.” In other words, a paragraph is usually focused on one specific aspect of your article, term paper, thesis, dissertation or book. As an author, it’s important to always think of each paragraph as an organic part of whatever you’re writing. Unfortunately, when students are taught to write stand-alone paragraphs in school, they are taught formulas: Write a topic sentence, give three supporting sentences, and then a conclusion sentence. In reality, it is not necessary to come up with a conclusion for each paragraph in an essay or book chapter; just end the paragraph in a way that completes the thought.

While it is common to quantify the number of sentences a paragraph should have (for example five, as mentioned above), in practice, this is not a hard and fast rule. Paragraphs of one or two sentences, depending on circumstances, can be more than adequate, though your professor might think otherwise. One of the most common uses of short paragraphs comes when dealing with dialog.

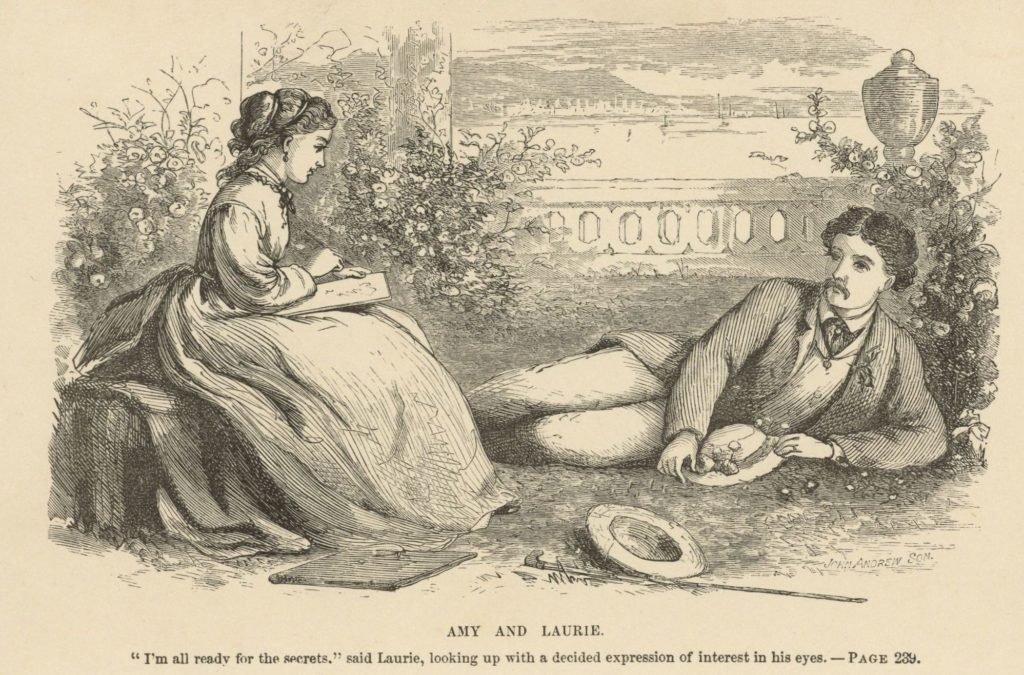

Screenwriters and playwrights don’t think twice about writing dialog in a rather straightforward manner, without any modification other than setting the scene. In writing prose, whether fiction or nonfiction, some sort of commentary is usually added. This can be as simple as something like “he said” and “she replied.” To illustrate a more literary approach, here’s a random sample from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women:

“That is the prettiest wedding I’ve been to for an age, Ned, and I don’t see why, for there wasn’t a bit of style about it,” observed Mrs. Moffat to her husband, as they drove away.

“Laurie, my lad, if you ever want to indulge in this sort of thing, get one of those little girls to help you, and I shall be perfectly satisfied,” said Mr. Laurence, settling himself in his easy-chair to rest, after the excitement of the morning.

“I’ll do my best to gratify you, sir,” was Laurie’s unusually dutiful reply, as he carefully unpinned the posy Jo had put in his button-hole.

It’s not uncommon in modern fiction for writers to use even shorter paragraphs for dramatic or poetic effect, such as this excerpt from Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief:

Just as the Führer was about to reply, she woke up.

It was January 1939. She was nine years old, soon to be ten.

Her brother was dead.

In this instance, each paragraph, despite its brevity, represents a complete thought, which would not be the case if all three were merged into one.

There’s nothing wrong with writing paragraphs of different lengths, whether short or long. Just make sure and be careful to make sure they contribute something to the overall impact of what you’re writing. In any case, if you’ve created long paragraphs that seem to go on and on, look for places to break them up.