Theoretical frameworks, according to a Trent University “Online History Workbook,” “provide a particular perspective, or lens, through which to examine a topic.” One might say they provide a ready-made set of questions to pose when trying to make sense of a particular data set.

It is a concept many tend to associate with science, as with Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, though they can be used in any scholarly discipline. (Their use is actually wider, but I won’t get into that right now.) The use of theoretical frameworks in science is easy to understand, though application to other fields, such as in the arts and humanities, can be difficult for some to grasp.

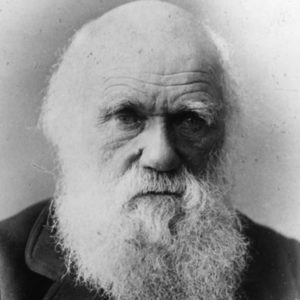

A scientific theory explains the evidence and allows one to make predictions about future evidence, and change or adapt as new evidence requires different explanations. For instance, in 1980 the father-son team of Luis and Walter Alvarez’s raised the hypothesis that the mass extinction of dinosaurs being caused by an asteroid impact 65 million years ago. This was something of a challenge to the then accepted view that evolution according to Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection proceeded in gradual increments. In the end, biologists were able to accommodate this into Darwin’s theory, which continues as the foundation for explanations biological evolution.

The theories used in writing about the arts, social sciences and humanities are not seen as readily verifiable as those in the hard sciences. However using a theoretical framework to understand literature, history and sociology in a more nuanced way. In fact, there may be a wide range of theoretical approaches which can be used to examine the same evidence, perhaps with equal validity.

For instance, Finnish scholar Yrjo Engeström in his article, “Activity Theory and the Social Construction of Knowledge: A Story of Four Umpires,” illustrates how the same event can be read differently, depending on your framework. He begins by citing H.W. Simons’ story about three baseball umpires who disagreed on

“calling balls and strikes. The first one said, ‘I calls them as they is.’ The second one said, ‘I calls them as I sees them.’ The third and cleverest umpire said, ‘They ain’t nothin’ till I calls them.’”

The differences, according to social psychologist, Antti Eskola, are as follows:

“The one who believes in the possibility of describing the world objectively says: ‘I whistle [i.e., call] the ball foul when it is a foul ball.’ The subjectivist who understands the constructive, observer- and instrument-dependent nature of knowledge confesses: ‘I whistle a foul ball when it seems to me that it is a foul ball.’ The third umpire for whom the world is socially constructed says: ‘The ball is foul when I whistle it a foul ball.’”

However, Engeström provides a fourth way using his own Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), which puts the game in a larger social context (i.e., baseball as what he calls an “activity system”) rather than being focused on the reactions of individual umpires.

How to decide which theory to use is something we’ll discuss in a future post.

When I was a kid, back in the dark ages, our teachers told us to use masculine pronouns when referring to a generic, unspecified individual.

When I was a kid, back in the dark ages, our teachers told us to use masculine pronouns when referring to a generic, unspecified individual. One of the most common problems in writing nonfiction, faced by students and professionals alike, is making sure your opening and closing paragraphs relate to each other. This is true whether the work is a 1,500-word term paper or a 120,000-word book. It is an issue I’m facing right now in expanding my PhD dissertation into a book. Not only am I enlarging the scope of my earlier work, I am using a different theoretical framework, which has made me look at what I wrote years ago in a different light. Fortunately, I have a year to fix problems and I have two crackerjack editors—my wife and the one assigned by the publisher—to help me.

One of the most common problems in writing nonfiction, faced by students and professionals alike, is making sure your opening and closing paragraphs relate to each other. This is true whether the work is a 1,500-word term paper or a 120,000-word book. It is an issue I’m facing right now in expanding my PhD dissertation into a book. Not only am I enlarging the scope of my earlier work, I am using a different theoretical framework, which has made me look at what I wrote years ago in a different light. Fortunately, I have a year to fix problems and I have two crackerjack editors—my wife and the one assigned by the publisher—to help me.