The selection of a citation style for your term paper, dissertation or journal article is often easy: Use what your professor, academic department or publisher mandates. Sometimes, you may have a choice: I used to allow my students to pick between MLA, APA and Chicago/Turabian; in such a case, select the one you are most comfortable with or perhaps flip a coin. In any case, you need to follow the style as closely as possible, as it otherwise might hurt your grade.

In academic and professional writing, it’s useful to remember, citations are designed to identify the sources of your information and/or ideas, including direct and indirect quotes (i.e., paraphrasing what someone else wrote). As Vickie noted yesterday, “Basically you must cite any time the question arises in the reader’s mind: How do you know that?”

Citation styles can sometimes seem rather arcane and petty. For instance, the APA Style Manual suggests using two spaces after a period, though most professional writers use only one. (Two spaces made sense in the days of typewriters, as it made manuscripts more legible; today’s word processing programs, which generally use proportionally-spaced fonts, made this practice largely obsolete.) For the most part, though, they represent a set of conventions which makes communication easier.

There are several ways to get help doing citations for your paper or book. The approach you use is up to you.

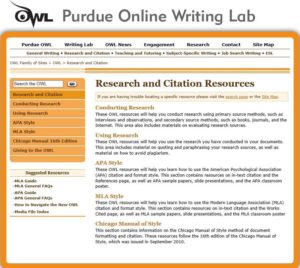

- College libraries often provide online guides to using the school’s approved citation styles, which can also be illustrated with YouTube videos. A popular one is Purdue OWL, hosted by Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab. They are particularly handy if you are doing citations manually for something like a term paper.

- Published style manuals, such as Kate L. Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations: Chicago Style for Students & Researchers. These are usually available at library reference desks. Buying one is only necessary is if you’re writing a thesis or dissertation, or doing a lot of scholarly writing.

- When in doubt, ask your instructor or, better yet, a librarian at your school or public library.

Digital solutions, aka bibliographic management software, are readily available in both commercial and free varieties. Some of the commercial programs, such as Endnote, may be free if you’re a student or professor at some schools. I don’t have time to go over them in detail right now, but here are a few options:

- The latest versions of such programs as Microsoft Word and LibreOffice Write have the capability of creating citations and lists of works cited (bibliographies). Bibliographic data has to be entered manually and they are somewhat limited in scope, but they can often get the job done.

- Zotero is a full-featured freebie from George Mason University. It began as a Firefox extension, but is now also available in a standalone version. It excels at easily capturing bibliographic information from websites and library catalogs. Like the next two entries, it can format citations in a host of specialized styles, including those required by journals like ACM Transactions on Computer Systems and Clinical Pediatrics. It’s also one of the two programs we use.

- Endnote is an oldie but goodie, which has long been a standard for many colleges and scholars. I use it because of its ability to modify citations to suite my needs; I sometimes use it in conjunction Zotero, which has its advantages. Endnote Basic (formerly Endnote Web) is a free online version of the program, which is somewhat limited (e.g., it only allows 50,000 references, only uses 7 basic citation styles and lacks the ability to edit citation styles). However, this might be good enough for those looking for a free alternative to Zotero.

- Citavi is a Swiss program that’s fairly new to the American market, but it’s a worthy competitor; however, it’s doesn’t seem as easy to modify as Endnote. If you’re not writing a book or dissertation, you might consider downloading Citavi Free, which allows you to use the full program gratis for up to 100 references.

Post last updated: December 2, 2016.