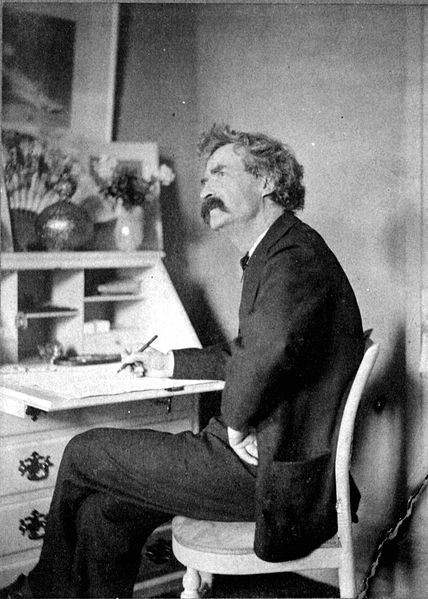

You don’t have to be a Mark Twain to allow your personal voice to come through as a writer.

At an art college where I used to teach, students were required to go on a field trip. As an incentive in my class, they had to write a 250-word report that would count for 5% of their final grade; I also guaranteed they would basically get an A on this assignment if they just finished it and handed it in. Interestingly, some of these reports were better written than their term papers. Freed from the necessity of conforming to their preconceived ideas of what an academic essay is supposed to be, they allowed their real abilities as writers to surface. More importantly, their personal voices came through.

Allowing what you write to reflect who you are and what you believe is a perennial balancing act for students and academics alike. But it is also an issue for people in a wide variety of situations—the businesswoman giving a keynote address at a dinner or writing copy for her company’s brochure; an aggrieved citizen writing a letter to their local district attorney; or an immigrant for whom English is a second language trying to write their resume.

Some editing services advertise they can transform a piece by an ESL author to make it read like it was written by a native speaker. To some extent, this is what we also do. But I don’t think it should be done at the expense of neutering who that person is. As a professor, one of the joys of working with international students was the added perspectives they brought to the classroom. And as a magazine editor, I likewise found the pluses of having contributors from around the world far outweighed the extra effort that may be involved in working with them.

Writing without fear can be especially hard for high school students writing their personal essays when applying to college. The hypercompetitive atmosphere surrounding the process can be very scary, which can lead applicants to be overly conservative. The resulting essay might seem to fulfill all the school’s requirements except one: the clear sense of who the applicant is. In other words, a lack of a personal voice, a quality admissions officers really do look for.

The one type of writing we have worked with that does not really suffer as much from artificial constraints is the personal memoir. These can be rather fun to work on. For instance, we once got a book written for family and friends (it was to be self-published). As such, the prose was casual and unforced, so we could concentrate on things like grammar and structure to allow it to breathe better. In this case, the author did not seem to understand how to break up their text into proper paragraphs (i.e., he made paragraphs that went on for pages, or run-on paragraphs). The results were very gratifying, and our job was made easier because the writer was speaking from his heart.